The Semmelweis Reflex

Our Tendency to Automatically Reject New Ideas

5 min read

“I won’t change my mind on anything, regardless of the facts that are set out before me. I’m dug in, and I’ll never change.”

Mac, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia

The Doctors’ Plague

In 1847 in Vienna, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis made a discovery that changed the medical profession forever.

He found the solution to the “Doctors’ Plague” - a devastating infection also known as childbed fever.

The discovery should have saved countless lives at the time.

But instead of being hailed as a hero, Semmelweis was ridiculed and ignored.

His advice was discarded, and the death rate from the Doctors’ Plague remained high for another 20 years.

Semmelweis had the right answer, at the right time, to a vital problem.

So what exactly went wrong?

Old Doctors, New Tricks

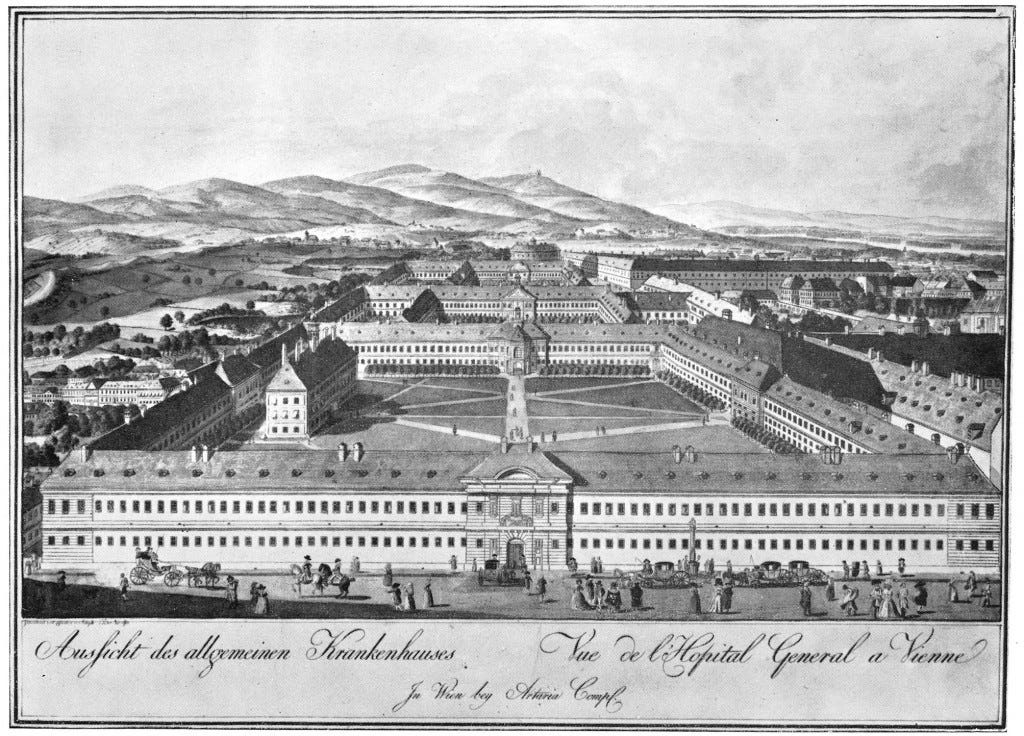

Semmelweis began working in the maternity clinic in the Vienna General Hospital in 1846.

He quickly became obsessed with a problem in the clinic:

One of the maternity wards had an unusually high mortality rate.

New mothers were dying from childbed fever with alarming frequency.

Why was this happening?

After months of observation, Semmelweis finally got an answer.

Doctors were unintentionally bringing bacteria from the morgue (where they performed autopsies) directly to the maternity ward, where they’d examine patients or deliver a baby.

No hygiene precautions were taken.

This was leading to high rates of infection and death during childbirth.

So Semmelweis suggested a simple fix:

Good hand-hygiene.

All medical staff were to wash their hands with a chlorine solution before seeing a patient.

Immediately the infection rate in the maternity ward dropped by 90%.

Semmelweis had discovered a way to save thousands of lives.

But despite the glaring evidence, his new theory was met with resistance from the medical community.

Leading medical experts dismissed and ridiculed Semmelweis.

The new theory didn’t fit in with the prevailing theories of the time, so it was ignored and rejected.

The Semmelweis Reflex

Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis died in an asylum for the insane in 1865.

His remarkable discovery, which could have saved lives, was mostly ignored by the medical community.

It wasn't until years later that his discovery got the recognition it deserved.

The "Semmelweis Reflex" had been born.

The Semmelweis Reflex describes our tendency to quickly reject or ignore new ideas which contradict pre-existing beliefs or norms.

Being open to new ideas is hard.

We tend to have an initial knee-jerk reaction against them. Especially when they challenge pre-existing norms.

History is littered with examples of the Semmelweis Reflex.

Like Western Europe’s rejection of the 8th century idea that Zero could be a valid number.

Or claims that the internet was just “a passing fad”.

And my personal favourite:

In 1920, the New York Times ridiculed physicist Robert Goddard, rejecting his claim that a rocket could work in the vacuum of space.

With little understanding, the NY Times instinctively dismissed Goddard’s new idea.

In arguably the most famous newspaper correction in history, the NY Times eventually acknowledged its error - just three days before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon.

But it’s not just at an institutional scale - we’re prone to automatic rejection of new ideas on a personal level as well…

Professional Stagnation

The Semmelweis Reflex can make us narrow-minded, and blind to change and innovation.

The result can be as mundane as a flippant rejection of a new gym programme or diet, but it can also impact the bigger things in life, like our personal finances:

We might reject the suggestion of a new portfolio allocation, even if the monetary and fiscal landscape is changing.

Or we might miss investing opportunities - reflexively rejecting ideas like 3D printing, NFTs, or cryptocurrencies.

More importantly, the Semmelweis Reflex can cause us to stagnate professionally.

Tech is changing working conditions faster than ever.

If we can’t suppress our tendency to reject new ideas or new methods of operating in our industry, then we’ll be left behind.

CPD and learning new skillsets are just part of the solution.

We also need to be on high alert for major industry changes.

I work in law. And it looks like robots are coming for my job.

It seems robots are snapping at the heels of a lot of knowledge workers - OpenAI’s ChatGPT has now passed the US Medical Licenses exam and an MBA Operations exam. Be very afraid.

But that’s a sidebar.

The point is, if we’re open to new ideas, we can position ourselves better professionally.

Keeping our Semmelweis Reflex in check means that we might have a chance to gain a first mover advantage, in our careers or industries.

At the very least, it reduces the chance that we’ll be left behind.

What’s the Fix?

How do we get better at embracing the new?

The Mere Exposure Effect.

We can fight bias with bias.

We tend to like things that are familiar.

And repeated exposure to something means it becomes familiar to us.

So by making an effort to get repeated exposure to new ideas or viewpoints, our brains might see them as less threatening.

Our Semmelweis Reflex is then less likely to kick in and make snap decisions for us.

Awareness and Humility

A simple framework for fighting the Semmelweis Reflex:

1. Intellectual Curiosity, a Growth and Learning Mindset

2. Humility

3. Awareness of the Reflex

The Bottom Line

We tend to struggle with new ideas that change the status quo.

Especially when these new ideas require a change in our behaviour.

Our reflex reaction is usually to resist.

But this can make our world very small.

And as Ignaz Semmelweis saw, it can even cost lives.

So the next time you come across a new idea that you’re tempted to immediately dismiss, put it in the maybe pile until you’ve had a chance to look into it a bit more…

And if you end up on the wrong side of the Semmelweis Reflex, take comfort in the fact that Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis eventually got the recognition he deserved.

Jack, do you personally believe this could possibly have taken place with Physicians, Scientists, tech, and subsequently the public more broadly regarding COVID treatment and prevention? It always seemed conspiracy-ish to me, but the longer the illness is circulating, the more I have begun to see areas where my initial impulse to dismiss any information contrary to the common narrative may have been short-sighted. There was a real component of social pressure, where even openness to contrary information placed you on the fringe of society.

Have you noticed a similar trend in yourself or others?